Richmond’s complicated relationship between geography and destiny

By Wendi Jonassen

An aerial view shows Parchester Village under construction in 1949. (Photo courtesy of The Richmond Museum of History)

Ten years ago, Rich Walkling, the business manager at Restoration Design Group, started a project to restore the mouth of Rheem Creek in Parchester Village.

The community of about 400 single-family homes, built in 1949 in Richmond’s first attempt at an integrated community, had started with the perk that residents could swim or fish in the nearby Breuner Marsh. But years of development have altered or destroyed most of the natural wetlands, including Bruner Marsh, and Rheem Creek now runs almost exclusively through manmade structures. Still, Walkling approached the restoration project with some concern.

“It is not addressing the immediate issues that these communities face – crime and poverty,” Walkling said. “I always felt a little like, what am I doing, coming over here and talking about restoring creeks?”

A development company resisted his restoration idea, but Walkling was more concerned with the community’s opinion. Creeks tend to go through the middle of a community, which means a conservation project can be incredibly intrusive on a neighborhood.

As with most restoration projects, Walkling invited the community to join him during the design and planning stages. Community response is normally a handful of people, he said. But in Parchester Village, almost 100 people participated in the restoration meetings.

At one of these meetings, he asked about doing environmental work in Richmond. The response was emphatic and validating. “If restoring creeks is good enough for people in Marin, it’s good enough for [Parchester Village],” he remembers hearing. “There is no reason why they don’t deserve that too.”

The project never came to fruition because the owners decided to develop the land instead. But while researching the Rheem watershed, Walkling and his colleagues found seven other restoration opportunities along the creek that continue to be focal points for conservation projects a decade later.

Over the last century, as industry grew and the population exploded in Richmond, conflicts between construction and restoration have been inevitable. Development and the natural landscape all over Richmond have been at odds — unnecessarily, some scientists and environmentalists now say. Flood control channels, levees and pipes under the city control the flow of water so effectively that it’s easy to forget the historical paths of Richmond’s creeks – or how that simple bit of knowledge, many ecologists say, could improve life for both people, and plants and animals, that live here today.

Parchester Village began its battle to development 10 years ago. It also provided a lesson for Walkling about the way the community values restoration projects. Bridging the gap between concrete and nature while understanding the history of landscape, development and its residents will be vital in determining the future shape of Richmond.

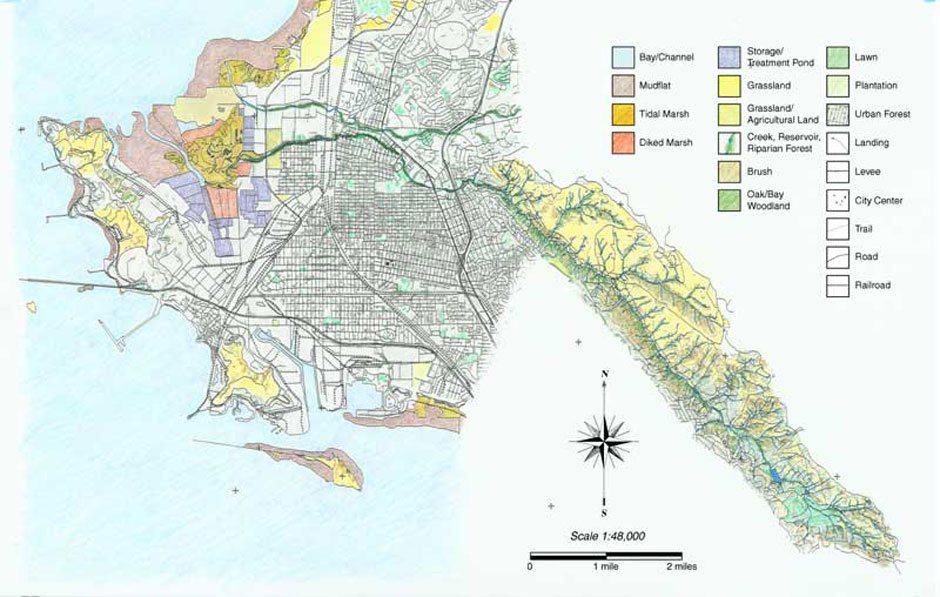

In 1901, Richmond’s population was around 200 people. By 1923, the population had exploded to 23,000 because of the growing railroad and oil industry. The population expanded again as immigrants flocked to work in the Kaiser Shipyards in World War II, and by 1947 the population was at 90,000 — nearly its present-day level. The new residents needed housing, stores, paved roads and general development.

The Kaiser Shipyards brought jobs and immigrants to Richmond. They also radically transformed the landscape. (Photo courtesy of Rich Walkling)

“We got busy modifying the landscape,” said Ruth Askevold, a GIS analyst at the San Francisco Estuary Institute, while speaking at a Watershed Conservation Symposium in Antioch in mid-November. “In short order, we got busy ditching, diverting, flattening, cutting through, building up, smoothing over, paving over, damming and draining. We bought, sold, cut down. We hunted, farmed, quarried and we mined. We made the landscape we have today.”

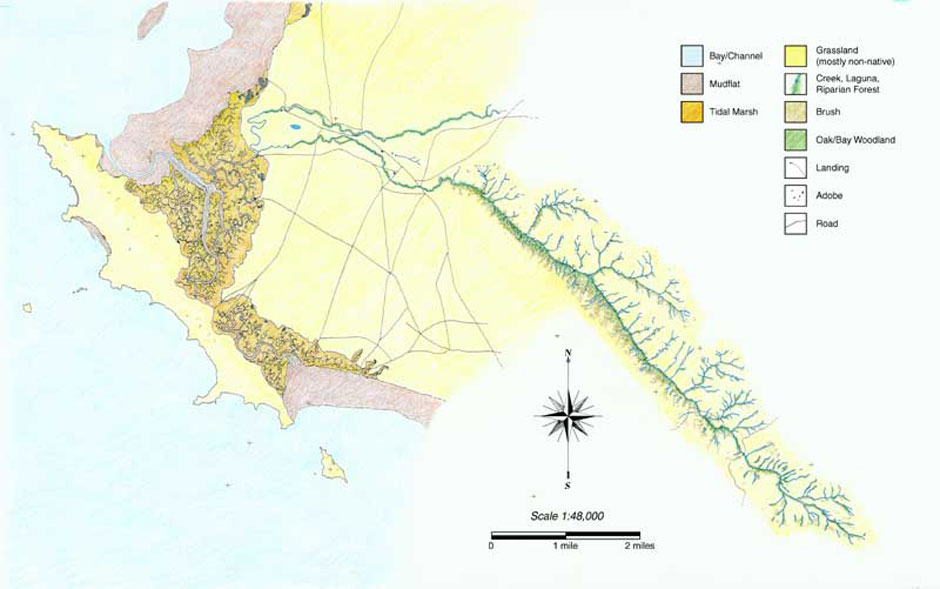

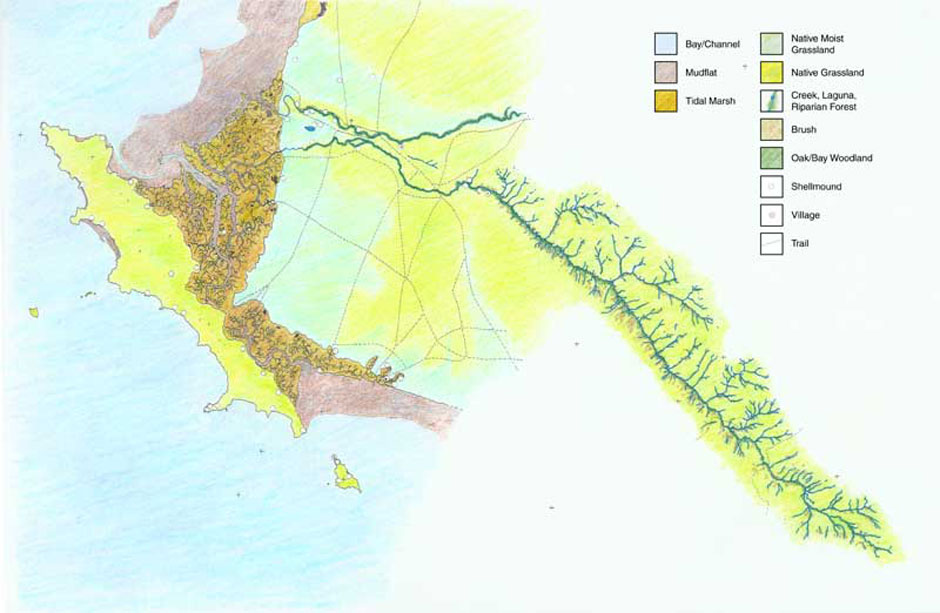

SFEI has done considerable work reconstructing the historical ecology of the watersheds in Richmond, going back to its first residents. Before Spanish settlers relocated and decimated the native population, the Huchians hunted and fished, and occasionally burned the land to encourage seeds to germinate, which they would then harvest.

“Like the rest of the bay, the area was rich in flora and fauna, until hunting decimated the population,” Askevold said. “Waterfowl were described as so abundant that they blocked the sunlight as they flew overhead. Elk and deer ran over plains.”

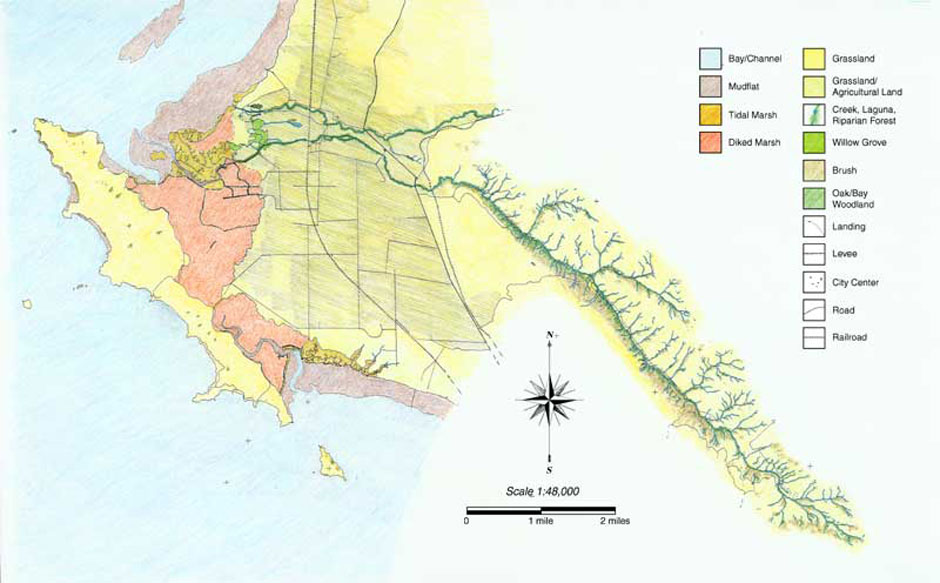

When settlers established the Mission Dolores ranching headquarters in the Wildcat Creek watershed in 1817, grazing changed the landscape. But the rapid residential development and industrial growth transformed the landscape much more quickly into what we have today.

In 1901, Standard Oil — now Chevron — bought 150 acres of marshland, which would become the largest refinery on the west coast today. They didn’t build in Richmond for the oil. They built the refinery in Richmond because the landscape provided an ideal setting.

After finding that the water at the Alameda shipyards was too shallow to support heavy boats, William Rheem, the manufacturing supervisor for Standard Oil, started scouting for the ideal location up the bay. He stopped at the end of the railroad line, just north of a railroad settlement, at 600 acres of marshland in what is now Richmond.

In the early days of oil production, explosions were much more common, if not expected. Since there are no trees in marshes to help spread fire, building a refinery on marshland was a precautionary measure. And with the marshland downwind from the bankers’ and investors’ homes in San Francisco, the land in Richmond was had all the right features.

By 1906, the refinery was one of the largest in the world. Today, it is the largest refinery on the West Coast.

The geography of the land invited specific development in Richmond, like refineries, which in turn, structured the history of its people.

Nowhere is the idea of landscape as predictor of development more evident than in North Richmond. Before the population boom of the 1950s, North Richmond had been a flood plain. San Pablo Creek and Wildcat Creek trickled together into a tidal marsh, which led into a mudflat and eventually into the bay. After a series of floods in North Richmond between 1951-58 destroyed property, the community developed a Flood Control Department, funded by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and the federal Soil Conservation Service.

The Flood Control Department began erecting levees, channels, drop structures, culverts and basins in the ‘60s, altering the landscape for the sake of flood control. The department now owns 72 miles of creeks and channels and 30 detention basins in the Contra Costa County watersheds.

While the Flood Control Department relies heavily on input from both the community and ecological assessments today, it wasn’t until the Clean Water Act of 1972 that organizations began considering ecological impacts of flood control. One of those impacts, engineers soon found, was that the newly designed creeks were rapidly removing water from North Richmond. And while that’s the point of a flood control channel, taking that water out has its own effect on the rest of the landscape and the animals and plants living in it.

Historically, in rainy winters San Pablo and Wildcat Creek would merge together, which is why North Richmond is now in a floodplain. During the dry summers the creeks dried up. In that natural cycle, there was little erosion or land loss, said Mitch Avalon, the deputy director of the Flood Control Department.

As people settled the land in that area, year-round flood control became a priority over natural ecology. But shifting priorities came with costs; it interfered with the life cycles of migrating fish and disrupted the natural erosion patterns.

Today, San Pablo and Wildcat Creeks channel separately into the bay, past a buried landfill and through constructed channels. Just above North Richmond, the water flows between two 10-foot-tall concrete walls, lined with graffiti, and under rickety railroad tracks. As the creeks approach the bay, they enter into the earthen levees, which may be mistaken as natural slopes of the land, but these slopes are just as constructed as the concrete levees. The creeks can only be seen through fences and over barbed wired, while buildings that house chemical companies sit on either side.

“We have overly designed our landscape to remove water and we may want to rethink it,” Avalon said.

Working within the natural characteristics of the landscape, while still ensuring that communities aren’t in danger of flooding, is one of the primary goals of landscape ecologists. The San Francisco Estuary Institute, with help from the Watershed Project, the National Heritage Institute the Flood Control Department and Contra Costa County, has spent considerable time and energy over the last few years poring over old documents to try to rebuild the watershed through time and to understand the historical ecology of the community.

For more information:

- San Francisco Estuary Institute Historical Ecology Program:

Wildcat Creek Landscape History - The Watershed Project

- Restoration Design Group

- Contra Costa County Flood Control District

The intention is not to try to rebuild the watershed as it was hundreds of years ago, said SFEI’s Historical Ecology Program Manager Robin Grossinger. Instead, this kind of assessment helps conservation organizations work with the community on flood control and restoration projects. For example: the Flood Control department has struggled to get plants to survive in its restored areas. The ecological history of the creek might offer an explanation and the proper habitat requirements for plants to survive.

“We scratched our heads and tried to figure out why our plants had died,” Avalon said. “But with historical ecology, we can go back and look at the landscape that was there before.”

Like most history lessons, understanding the past of the land will help with plans for the future.

“It helps us understand how these systems were designed. We find that we learn from that information. We can pull out lessons, insights, ideas and strategies,” Grossinger said. “What does the next century look like? How do we make our systems more resilient to climate change? How do we find the smart things that we can do within the context of a highly developed, populated landscape?”

SFEI researchers pored over 6,000 historical documents, maps, photographs, surveyor notes, landscape paintings, journals from explorers and newspaper clippings, compiling them using a geographic information system, or GIS, as a holding tank to assemble and compare the data.

Looking at writings from 1866, the SFEI would find quotes like “it is a sandy, hard soil, with a sandy land” and “a young man was killed by a Grizzly bear in a dense forest” to help understand the flora and fauna of the area.

The old maps would describe a distance as “a half-day ride” from here to there, which were pretty obscure measurements. But with the help of pictures and research, those distances can be estimated much more precisely, with accurate GPS coordinates to describe them.

The researchers also untangled many sources of information. Old photos of picnics, with specific oak trees and mountainous landscapes in the background, became valuable sources of insight into history. The team assembled more than 300 aerial photos from 1939 to produce a continuous mosaic of images.

“None of this is as easy or tidy as the neat stacks of maps make it appear,” Askevold said. “We spent a considerable time sorting through data, understanding our sources, interpreting the information and looking for agreement and disagreement in maps and materials describing the same data.”

The Watershed Project revels in collecting oral histories, said Femke Oldham, the outreach program manager at the Richmond-based environmental group.

While at the watershed symposium, she overheard a man who had been born in the watershed talking about a time, decades ago, when the dam flooded and he witnessed steelhead migrating upstream, jumping out of the water at 23rd Street. She probed deeper, asked more specifics about the location and the year.

Litter and chemical runoff make the area inhospitable to steelhead today. And without trees in the region, the stream’s temperature increases, changing the micro-ecology and making it more difficult for the migrating fish. There is also a drop structure at 23rd Street, a manmade concrete waterfall intended to slow down the flow of the creek that acts as a barrier.

Oldham has only seen crawdads at that spot, which sees more litter than aquatic life today. But the knowledge that it’s changed so dramatically within a time frame less than a human lifetime also suggests that to allow some fish to return to the creek might require fewer – and smaller – changes than you’d think.

Reconstructing the ecological history of Richmond is difficult, but the real challenge is fundraising. Money – finding it, and spending it – is the thread that runs through a number of ongoing North Richmond environmental projects:

+Prior to 1978, citizen committees in each watershed could plan their annual budget based on what was needed. The board would adjust the tax rate in that region to adjust the finances to fund conservation and flood control projects. In 1978, Prop 13 froze property taxes, which required that the board set taxes in each watershed zone. After a drought in the Wildcat Watershed in 1976 – a drought year when there was no flooding danger — the board set the fees and taxes to almost zero, Avalon said.

“Now, we have $70,000 a year to manage the watershed from the bay to the railroads,” said Cece Sellgren, an environmental planner with the Contra Costa County Public Works Department.

That‘s tough to work with. Just dredging the small ponds that collect soil and other sediments, for example — which the department must do every few years — can cost hundreds of thousands of dollars.

+After Hurricane Katrina, FEMA began reconsidering its standards for levees. After a $640,000 analysis, FEMA decertified the levees on Wildcat and San Pablo Creeks just above North Richmond.

While the community is in no danger of flooding with the levees as they are now, without FEMA certification the neighborhood will be reconsidered as a floodplain, meaning that insurance for homeowners will rise and developers may not be able to get permits to build there.

Recertifying the levees would be a multimillion-dollar project, leaving North Richmond stuck between extra insurance or permitting fees and massive capital improvements.

+The Flood Control Department is working on fixing fish ladders in the San Pablo/Wildcat watershed to try and allow steelhead to return to the creek. The ladders are a series of baffles that allow the fish to rest as they swim upstream against the current.

“Those baffles create little spaces that they can chill in for a minute and then they can shimmy their way up a little farther,” Sellgren said. “And they are really important when you have a concrete-lined channel because water in concrete channels moves much faster than naturally or grass lined channels.”

Fish don’t like swimming in the dark for very long, Sellgren said, which means that the culverts and underground channels further constricts the path of the migrating steelhead.

The Urban Creeks Council is also working on a Wildcat Restoration Action Plan project to “daylight” some of Wildcat Creek, which means that they will make some of the underground portions of the creek flow above ground.

“Daylight of two culverts … presents a major opportunity to open habitat for the steelhead lifecycle,” the Urban Creeks Council wrote in its summary of WRAP. “As a keystone species for the watershed, the presence of a viable population of steelhead is an indicator of watershed ecosystem health.”

The historical assessment — of the community, the steelhead population and the ecology — is crucial for these kinds of projects. Understanding Richmond’s history helps build a more responsible future.

Even with its extensive reports and ambitious projects, the Flood Control Department won’t move forward without consent and feedback from the community first.

“Nowadays we work with the community to come up with a vision for the plan,” Avalon said.

The community’s input is as important, if not more important than restoring a watershed to its historical condition, Sellgren said. “These are disadvantaged communities, and in general, when you don’t have enough food to eat, you tend to focus on those economic justice issues, as opposed to ecological issues,” she said.

But ecological and economic justice issues aren’t mutually exclusive. Levees affect flood control and insurance rates. Geography invited a refinery that has, in turn, molded the landscape and affected the residents. A drought more than 30 years ago still limits the funds available for projects.

Rich Walking works on environmental restoration projects throughout the East Bay, and describes Richmond as the most unique place to work. Since residents have first-hand experience with pollution, he says, they feel a strong sense of connection to their land and home and a need to protect it.

And as Walkling found when he first met with Parchester Village residents 10 years ago, an area that’s been developed isn’t necessarily an area that doesn’t care about its landscape – its past, or its future.