Yet in the rooms around mine, 53 women and children rested for the night. One of them called it “one of the safest places on Earth.”

Before coming to the United States from Singapore in August, I worked as a crime and court reporter, and shelters like this one don’t exist. Back home it is almost illegal to be homeless. People idling in public places can be taken by policemen and placed in welfare homes, while awaiting questioning if they look like they are unable to support themselves or prove they have a home. Leave a welfare home you have been assigned to and you can be jailed for six months. And campers need to apply and receive a permit the day before they can pitch tents in selected areas in parks.

I was thinking about this while cycling around Richmond one day, when I stumbled upon the Bay Area Rescue Mission. That there had been an increase in the number of people seeking shelter quickly came up during conversation with staff members. Winter was approaching and there was insufficient space to accommodate everyone. The cold added one more element of unfamiliarity, one more thing different from home. Located near the Equator, my island-country is hot and humid all year around.

While I continued to report in Richmond, I began to look for homeless people instead of avoiding their eyes. It soon became clear how many there were, and I quickly became interested in the stories behind how they ended up homeless and how they were surviving. They couldn’t want to be there, I thought. Where could these people go from there and what were the cracks they were falling through?

I decided there was no better way to start deciphering the homeless situation in America than to live for a few days as they would.

Things fell into place when I called Debra Anderson, vice-president of community relations at the rescue mission, a few days later to find out if she could speak with me about her experiences in working with the homeless. Though keen on helping me stay at the shelter, Anderson told me there might not be space at the shelter as they were usually full. I quickly said I could bring a sleeping bag.

After listening to everything I had to say, Anderson, who is also the wife of Rev. John M. Anderson, the president of the Bay Area Rescue Mission, told me she would call me back in 10 minutes. Two phone calls later, I had permission. And I didn’t need to bring a sleeping bag.

Cycling to the Bay Area Rescue Mission at 10 p.m., I passed shadows by the roadside that called out and wolf-whistled at me on my cream white vintage Raleigh. I could not have pedaled faster.

The shelter was dimly lit and quiet when I arrived. Everyone but staff member Maxine Mars had gone to bed and after taking some sheets and towels from a laundry room on the ground floor, she showed me to my room. We exited the living room through a back door, reentered the building through another door, climbed two flights of stairs, went through two more doors and made three turns before arriving. I wondered to myself how I was going to find my room in that maze over the next four days.

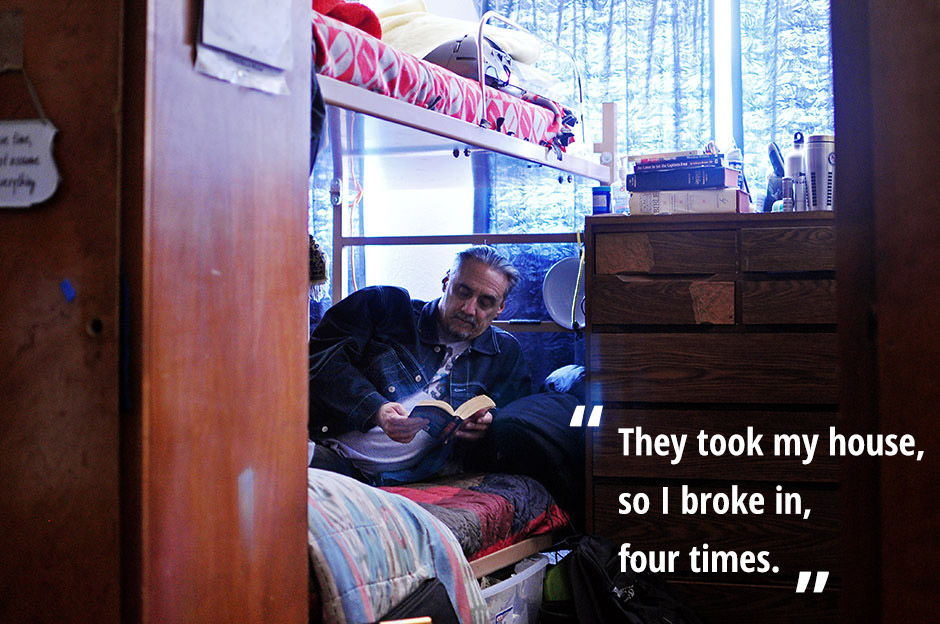

My room, a typical one for a mother with young children living at the shelter, was more spacious than I had expected. It had a twin bed under a window on one side and a bunk bed against a wall on another. There were also two mismatched shelving units and a study table. Mars later showed me the common bathroom and shower stalls just outside my room, which was shared by all residents in the wing.

After she had left, I washed up and put a set of donated red sheets on the twin-sized bed. When I tried to close the window as it was getting chilly, I found out that it was broken but decided to just roll up tighter in my blankets. After all, it wasn’t the cold that was going to keep me up. I continued staring at the ceiling while the trains continued pulling in one after the other and the dogs went on barking.

The only other occupant in my wing was Bernita Medlock, 44. Medlock, who had been informed of my arrival, shared a room with her two-year-old daughter, but I did not see either of them on my first night at the shelter.

The next morning, we met outside her room, two doors away from mine, while I was waiting for the wake-up call Mars had told me about the night before to come on over the intercom. “Rise and shine everyone, it is now 13 minutes past 6 a.m. Rise and shine, it is now 6:13 a.m. …” By 7:30 a.m., all of the women and children had gathered in the living room and we walked over to the dining hall in the next building for breakfast.

At breakfast, I took a seat with Medlock and her daughter, a curly-haired dark-skinned girl with full cheeks. Halfway through the meal, Medlock handed me an envelope. “My graduation speech,” she said.

Medlock is into her 19th month of a two-year recovery program at the shelter. While the program was shortened to a year earlier this year, Medlock decided to stay on the program she signed up for. “I need to show myself I can do this,” she told me.

The Bay Area Rescue Mission Recovery Program is a residential program with six areas of recovery focus - the individual’s job readiness, stability, fitness (both physical and emotional), financial, academic and spiritual development.

People can also stay at the rescue mission if they need emergency shelter, but most of the occupants on any given night are participating in the recovery program.

Upon completion of the recovery program, participants tell the story of their journey at a graduation ceremony.

I opened the letter from Medlock after breakfast and in the first paragraph of her speech, she thanked her mother for her prayers, and God for deliverance from “jails, institutions, suicide and death.”

The two-page speech is a summary of 20 years of Medlock’s life as a drug and alcohol addict. While everyone was waiting for the lunch walk to the dining hall one day, I asked if she could tell me more about her story.

“Homeless, hopeless, I’ve been there. It’s a deep, dark hole,” she said. “I’ve worked in all the fast food restaurants you can think of. But every penny I made, I spent on drugs. I didn’t see sense in paying for a room because I was constantly chasing my high, and when I was high, I just ran up and down the blocks.”

Medlock told me that she cut herself off from her family in Richmond in her early 20s because she was ashamed but unwilling to quit her addiction. She then took to the streets of San Francisco to reduce the possibility of running into family members. There she created a new family for herself from friendships forged on the street. But all of them, like her, were hooked on crack cocaine, and they encouraged each other’s addictions.

After being released from jail in 2010 for possession of multiple kinds of drugs, she soon found herself as a single mother without a cent. It was her mother who brought her to the shelter last year to join a recovery program and “learn to be an adult.”

Medlock’s success in the program has been recognized and she now has a logistical leadership role at the shelter.

As she spoke about her past, her daughter, oblivious to the gravity of the story being told, alternated between spinning in circles in the middle of the living room and running over to climb onto her mother’s lap. After being interrupted mid-sentence several times, Medlock raised her voice and told the girl to stop playing. The two-year-old stopped in her tracks, tilted her face slightly downwards and pouted her lips while her wide eyes looked up to watch Medlock. It wasn’t long before both of them started laughing and the girl ran over to climb back into her mother’s lap. This time she stayed there.

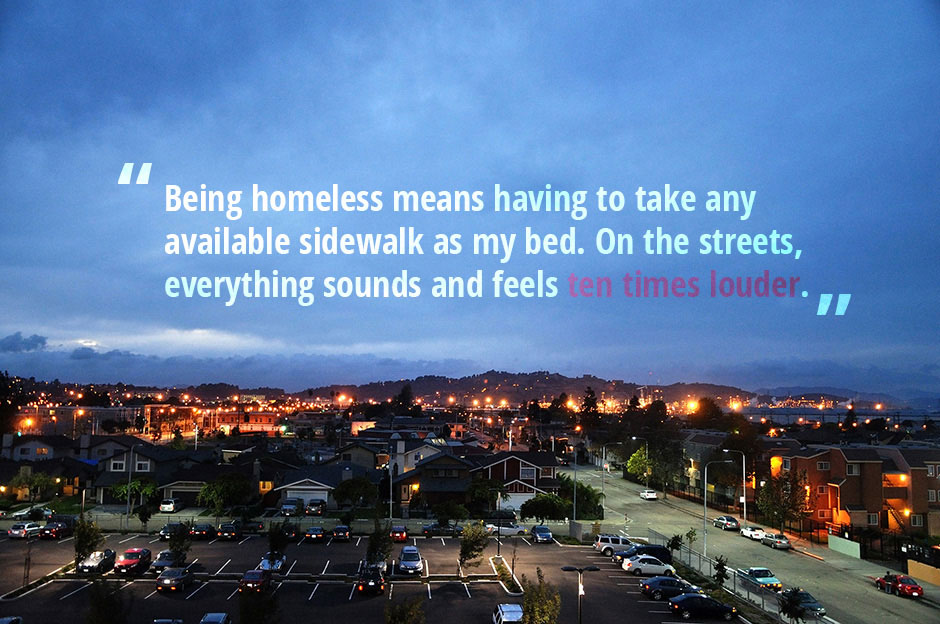

“Being homeless means having to take any available sidewalk as my bed. On the streets, everything sounds and feels ten times louder,” Medlock said. “Now, I’m thankful to be here with my baby girl.”